3. Anger

What?

We're all angry

Anger is not an easy topic in today's society. The cliché "I'm not

angry, I'm disappointed" is a good case in point. People seem to

see anger as a sign of moral weakness, as a base emotion that they

are clearly above. In reality, we're all angry all the time, if

you really think it through.

Let's look at a couple of examples.

1.

A junior engineer is getting chewed up regularly by a certain

senior colleague during code reviews. They can usually

acknowledge that their code certainly has room for improvement,

but they feel very frustrated by the way the message is

delivered.

2.

A project manager asks an engineer to "quickly" implement an

"import from CSV" feature for a user database. There is no

specification about which data should be imported (name,

address, email, ...), about access rights (universal,

administrators only, ...) or UX. They can see the need for the

import feature, but are utterly confused as to what is expected

from them.

Image by

@trainingsbyromy

on Instagram

Image from

"Animal models in psychiatric research: The RDoC system as a new framework for

endophenotype-oriented translational neuroscience", March 2017, Neurobiology of Stress 7, DOI 10.1016/j.ynstr.2017.03.003

3.

An open source maintainer sees a bug notification appear on

GitHub. The bug description is very accurate, including the

necessary steps to reproduce the bug and the expected

behaviour. Nonetheless, they spend a long evening looking for

a fix and eventually go to sleep without getting any closer to

a solution. They feel extremely disappointed with their

progress (or lack thereof) on the bug.

I've used different adjectives to describe the people's emotions

in the above — frustrated, confused, disappointed —

but ultimately, these can all be replaced by "angry". We like to

tell ourselves and the outside world that we are frustrated by a

colleague's lack of empathy, but we cannot deny that on a basic

emotional level this stirs up our anger. The same goes for the

confusion about the manager's feature request, which only thinly

veils our anger at their superficial work. And in the last

example, we saw disappointment that is nothing but the worst

type of anger there is: anger towards ourselves.

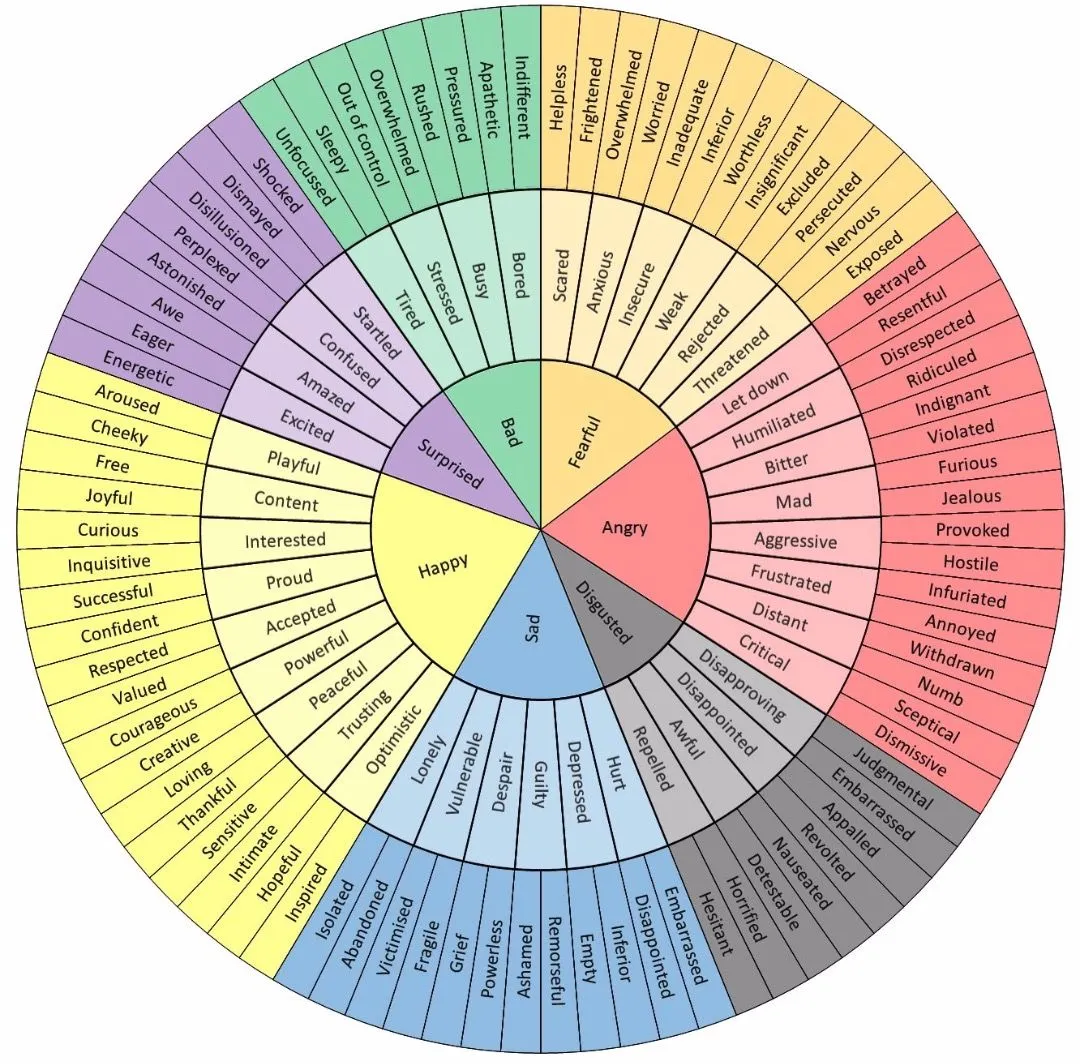

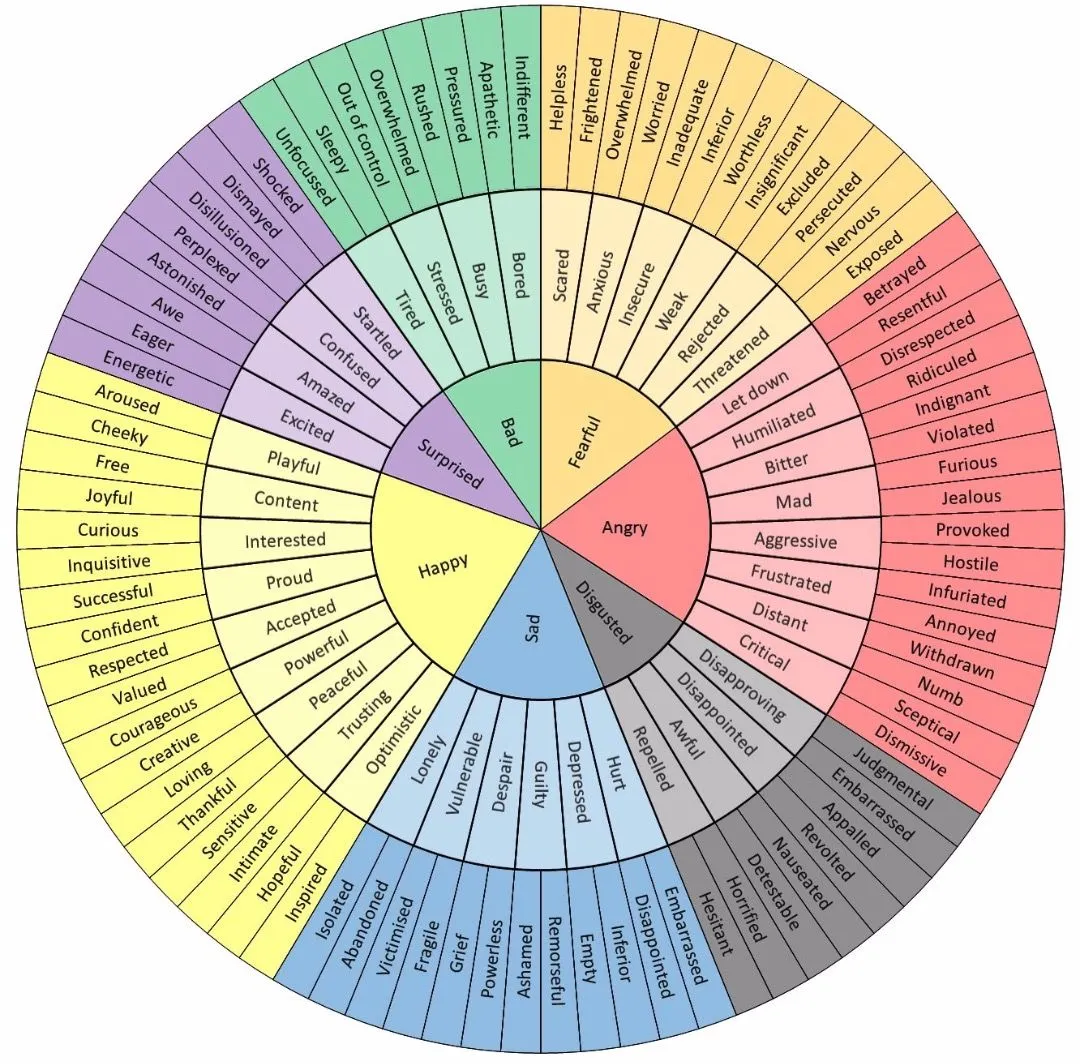

Wheel of emotions

Just look at the

wheel of emotions,

which is sometimes used in

affective science, and see

the wide range of emotions that are basically anger:

Physiology of anger

For all the social stigma, anger is one of our

primary emotions, which we will discuss at length

later on in this chapter, and we should not deny it. All

animals, including humans, get angry and display the

accompanying physiological effects of it, which is basically the

same as the stress reflex.

So everyone gets angry but how we display this anger differs

very much from person to person. A few people get openly angry

regularly, but more often than not people act

passive-aggressively. Many also feel shame or guilt, which is basically

anger directed towards ourselves. Still others turn their anger

into control mechanisms or avoidance behaviour. For some, anger leads to

certain, often very strong, beliefs or convictions. In extreme

forms this can take the form of religious extremism or

conspiracy theories, but we see it often in moderate forms too.

A good example is the anti-vaxxer community whose beliefs tend

to be fueled by anger towards politicians or doctors who wronged

them in the past.

Just like stress, anger needs to be released from the body, lest

it cause serious physical harm. Whether we are aware of it or

not, prolonged anger causes tension in the body that quickly

builds up and often gets released only when things turn really

bad. And often, people very much deplore such an outburst of

bottled-up anger and the things that they say or do in this

state.

Venting anger

Venting anger, however, has tremendous benefits for the mind and body. As we will discuss later on, it is an integral part of dynamic meditation. This might seem unusual or scary at first, but it is actually a very logical response that we see in many other circumstances too.

For instance, many people will know the

haka as the

dance performed by New Zealand's national rugby team the All

Blacks to challenge opponents before international matches.

Haka are often performed by a group, with vigorous movements and

stamping of the feet with rhythmically shouted accompaniment.

These ceremonial dances have been traditionally used for a

variety of social functions within

Māori

cultures. Interpretations vary, but most agree that seeing them

as "war dances" is a limited view. While there are war haka (war dances

exist in many cultures), other haka have been called

"celebrations of life".

Just look at this beautiful wedding haka:

Whether the purpose of the haka is for warriors to proclaim

their strength and prowess in order to intimidate the

opposition, or for families to mourn the dead or celebrate the

living, it is clear that the vigorous movement of the dance and

venting one's anger helps the performers to

cope emotionally.

Therapeutic value

Becoming aware of our anger and adequately dealing with it, also

has great therapeutic value. At first you will learn to see how

much anger you harbour towards others, which will already help

you a lot simply by raising your awareness and understanding

your emotions. But after a while, working with anger also raises

an important measure of accountability. Although

our anger is directed towards others, we realize that it is

we who are angry and that it is our responsibility

to do something about it. Facing anger is a great way to acknowledge your mistakes. Anger is also closely

related to fear,

so finding out what we are angry about, teaches us more about

our fears.

Why?

Personal growth

Why are we devoting so much attention to anger? A first, more

practical reason is that in my experience anger is one of top

factors that impedes our personal growth. Whether it be private

or professional, anger in all of its forms, including silent

resentment or passive-aggressiveness, leads to conflict and

impedes any kind of development or success. Remember the IT guy

from Jurassic Park, whose anger with his boss eventually caused

the cascade of events that ended up with the dinosaurs being

released into the jungle? It's a cliché example, but I am

convinced that anger stands in the way for very many people.

Facing anger towards loved ones or co-workers might be difficult (people seem to think that acknowledging

anger is like admitting defeat) is the best way to learn to say no, because when you let go of anger, you

will be able to say what you want from a place of quiet resignation instead of anger.

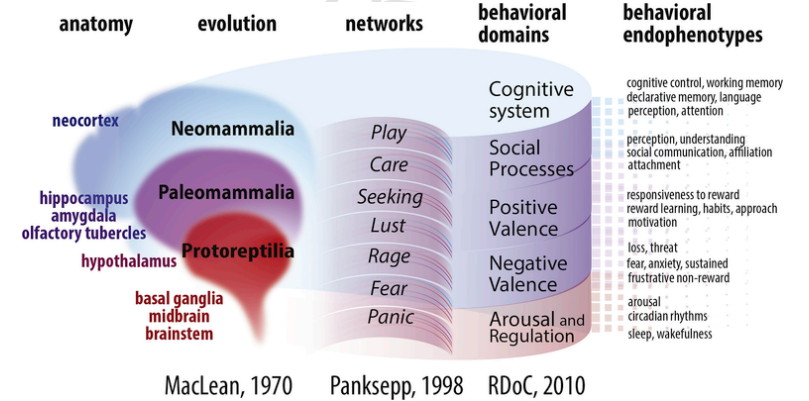

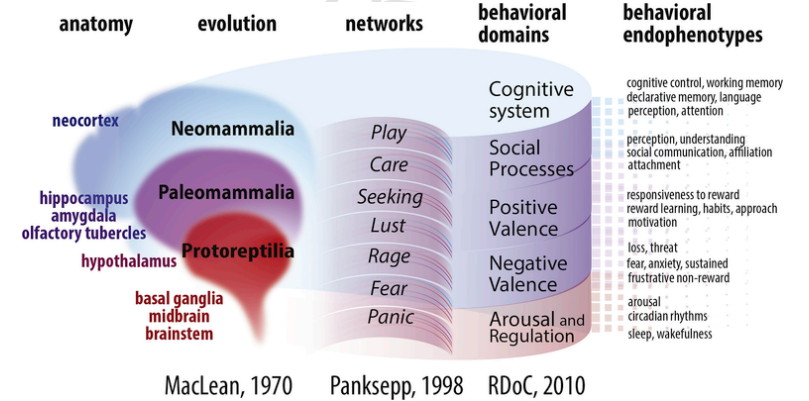

7 affective systems

A second, more fundamental emotional reason for our attention to

anger, is that anger is a primary emotion that permits us to

understand the whole spectrum of basic negative emotions. Anger

masks fear and fear masks grief.

In order to understand this, we need to introduce the concept of

the 7 primary affective systems as developed by

Jaak Panksepp Ph.D., the founder of

affective neuroscience.

In this TEDx-talk, you can see Panksepp introduce his work:

Panksepp's empirical studies of both animal and human emotions and neurology carved

out seven biologically inherited primary affective systems:

- fear (anxiety)

- rage (anger)

- panic/grief (sadness)

- lust (anger)

- care (nurturance)

- play (joy)

- seeking (expectancy)

As you can see, three of these are negative, i.e. they cause

unpleasant feelings and thoughts, and three are positive. One, i.e. seeking, is more neutral,

functioning as a kind of playmaker that determines the direction of our actions.

UNIX of emotions

Dr.

Tom Herregodts, who has

been using affective neuroscience in his psychiatric practice for over 25 years, often calls these 7

primary affective systems the "UNIX of our emotions", because in and of themselves these systems

work quickly and flawlessly. When an animal or human engages in sexual activity, it will produce the

neurochemicals and therefore experience the feeling of lust. When they encounter a predator, the same will

be the case for fear. In this way, these systems are certainly not inherently "negative" or "positive".

They all have their function. It is only normal to feel grief when a loved one dies, for instance.

The affective systems, which Panksepp associates with distinct regions of the brain, function through

various neurochemicals:

- adrenaline a.k.a. epinephrine (excitement, fear, ...)

- cortisol (anxiety, displeasure, ...)

- serotonin (mood, reward, ...)

- endorphines (pleasure, well-being, ...)

- oxytocin (bonding, connection, ...)

- dopamine (drive, motivation, ...)

As with the affective systems, the role and function of these neurochemicals is complex and often

double-edged. For instance, while

cortisol is sometimes called the "stress hormone", it is vital for basic bodily functions like waking up.

However, it is well-established that a chronic elevation of those

associated with the negative systems

or a surplus at the wrong time (e.g. too much adrenaline/cortisol when we go to bed) or

extreme spikes is detrimental, not only for our mental, but also for our physical health.

As already discussed, the negative affective systems provide a normal and even necessary component of our

emotional life, but when they go into overdrive things get problematic. Panksepp discusses, for instance,

various stages of anger, such as irritability (small), loss of impulse controle (medium), and vengeance

(high). The same goes for fear with worrying, anxiety, panic and finally psychosis.

From negative to positive

A healthy emotional life requires a balance between the positive and negative systems. A happy

emotional life can be defined as one that is directed (seeking) towards the positive systems, more than

towards the negatives. Let me give you a concrete example of that.

Imagine a day at work where you get assigned a particularly vexing bug ticket. You spend the whole day

trying to figure out what is going on, but without much avail, while at the same time people are asking

you questions about your progress. Under such circumstances, many people's seeking system will

automatically direct their emotions towards the negative systems, such as rage (anger towards colleagues

and themselves), fear (anxiousness about not getting the problem fixed) and sadness or even panic.

In another scenario, you wake up on a Sunday with a brilliant idea for a pet project. It is quite a bit

out of your comfort zone, but you soldier on and are happy to spend the day coding, even though you

cannot

implement everything you planned without further study. You contact a friend who knows more about the

topic and you spend up chatting a whole hour about your idea. For most people, this will active the

positive systems like play (hacking away at a problem), care (connecting with your friend).

In both examples, however, the actual work you are doing is very similar: trying to solve a

difficult software issue and discussing it with peers. The only difference is the affective systems that

get activated. This shows that if you would only succeed in deactivating the negative systems (anger,

fear, sadness) you could experience your work day with the bug ticket in a completely different way!

How?

We will discuss the 7 affective systems more in depth in the final chapter on burnout. For now it is high time that we returned to dynamic meditation,

which

lead us to talk about anger in the first place.

Dynamic meditation

In the previous chapter, we already introduced dynamic meditation as a way to rid the body of stress and

tension, and to to emotionally reprogram the fear memory. You could see a couple of examples of the

technique there, but we still need to discuss it in full.

Theory

1. Dynamic meditation starts with recognizing tension. As discussed, anger is often a good

way

towards emotional awareness.

Awareness of anger leads to awareness of fear, and

then to grief.

2. After becoming aware, we need to work with the

body to neutralize this tension and fear. We've already seen several techniques for that in the

chapter on stress, but what is important here to add, is the component of anger.

Stirring up and venting anger is the best way to bypass our cognitive system and access the animalistic

part of it. Remember, fear resides in the limbic system which is part of the palaeomammalian complex. This is why the best techniques for

releasing tension in dynamic meditation are very primitive, physical and animalistic: sighing, shouting,

shaking your body,

hitting a pillow, stamping, jumping up and down hysterically, ...

3. Of course, it takes time for our body to unlearn fear like this. Fear doesn't

just disappear from your limbic system. For centuries, this

system's job was precisely to help us survive by remembering

menacing smells, sights, sounds, tastes or situations. But with

honest effort and repeated practice, it is certainly possible to

silence the negative affective systems and thereby give room for the positive ones.

4. Then we are ready for the emotional work, i.e to face our fears.

We go back to a moment in the near or distant past where, for

example, we felt silenced, missed recognition, were afraid but

could not express an emotion, and so on. At such a moment we have

learned (by society) to bottle up our anger and unconsciously tension has

been stored in our body. In dynamic meditation, however, we

can turn the impotence of such a moment into strength by

discharging the anger and tension of the moment in a healthy way.

In this way we succeed in therapy where we failed in real life. Peter A. Levine, the creator of so-called

somatic experiencing, calls this

"succesful escape" and "empowerment". It is a way to reprogram our emotional memory with positive

experiences, which we have already discussed as a well-documented way to overcome fear.

5. In addition to bodily movements, the use of our voice is also

important. In addition to holding back anger, we have also learned

to bite our tongues and to interiorize not only feelings but also

words. That's why it's important to get those words out in therapy

and to shout out the words or sounds that you couldn't voice at the

time of the injury. By using your voice, you take your own place.

6. In this way, succeed in not only

releasing tension and erasing fear, but also emphasizing our self-esteem and

strength. During dynamic meditation, we therefore not

only shout: "Fear, get out of my head!", but also "I have the power!" or "I'm worth it!". Including such

positive affirmation is a key

aspect of dynamic meditation.

Practice

I realize that was a lot of theory. To boot, it probably seems and feels a very strange thing to do. So

let's have a look at a couple of practical ways of doing dynamic meditation.

The next videos (again you'll need subtitles) offer three different examples of dynamic meditation. The

first mainly uses bouncing and

some Qi Gong techniques. The second is an example of how to do dynamic meditation if you can't make a lot

of noise (wringing a towel). The third is an example of full-blown meditation, using a tennis racket to

hit a foot stool.

Exercise

Unsurprisingly, this week's exercise is about putting dynamic meditation into practice. How you do this,

is up to you. You can follow the "Hulk" or "Thor" protocols you have seen in the videos above, or if you

have a tennis racket and something to hit (a foot stool, a pillow on the bed, ...), go for it. There's

very little you can do wrong, except for directing your anger towards yourself.

Rules

Here's a few important rules to take into account when you are doing dynamic meditation:

- Practice alone

- Start with a maximum of 5 minutes

- Keep an open mind and give the practice an honest try

- Let go of any shame, prejudice or assumptions

- Never direct your anger towards yourself

- Never direct your anger towards others except during meditation

- Stop if you feel physical pain

- Continue if you feel fear, anger or sadness!

- Persist

- Experiment

Inspiration

If you want to learn more about anger, the 7 emotional systems, affective neuroscience or dynamic

meditation, you can find more information in the following resources: